Archaeology Blog

Of Parasols and Umbrellas

In August of 1822, Reverend S.A. Bumstead of Maryland was traveling in the Charlottesville area and happened to see Thomas Jefferson out for a ride. According to the Reverend:

“He was mounted on an elegant bay horse going with speed- and he had no hat on but a lady’s parasol, stuck in his coat behind, spread its canopy over his head…I am told he always rides in this manner during the summer without any hat…” (Notes and Queries 1916: 310-311).

In this rather amusing anecdote, Jefferson adapted the typical use of a parasol- creating shade- to riding a horse, where a hat was likely to be blown off by the wind. George Washington also made use of an umbrella while riding, fixing it to the bow of his saddle (Chernow 2010:29). For more detail about parasols and umbrellas at Mount Vernon, including a detailed analysis of parasol tips, check out the Mount Vernon Mystery Midden posts here, here, and here.

Parasols and umbrellas are an ancient accessory utilized by persons of importance in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa. Images from Ancient Egypt and Assyria document the use of fabric-covered sun shades held over members of royalty by servants. Not only did these devices shade these individuals, they also communicated their status and authority to observers (Ross 1994). To learn more about ancient uses of umbrellas, and see some excellent images, take a look at Stewart Gordon’s article here.

The English word “umbrella” is derived from “umbra,” Latin for shade or shadow. “Parasol” is derived from the Latin for sun, “sol.” These two terms were used without distinction until the mid-1700s, at which time umbrella became associated with an item meant to keep off the rain, and a parasol a feminine accessory for shade from the sun (Farrell 1985; König 2005).

In the Middle Ages and Renaissance parasols, as well as larger multiple pole canopies, were utilized by the Doges of Venice and the Pope (Crawford 1970). Other individuals of social and economic status began utilizing parasols in the mid-1600s, most likely the result of influence from China and India. While utilized as an ungendered symbol of authority and status elsewhere, in Europe umbrellas/parasols were considered to be a woman’s accessory throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Sangster 1855).

This image of Marchesa Elena Grimaldi of Genoa was painted in 1623 by Sir Anthony van Dyck, a Flemish artist most famous for his role as a court painter for Charles I of England. While the colors in the background and fabric of her gown are rather drab, the bright red parasol, carried by a servant, and her matching cuffs stand out in the image. The diagonal tilt of the parasol also adds drama to the composition. Parasols also appeared in the personal collections of Mary, Queen of Scots, Elizabeth I, and Victoria, who had hers lined with chain mail to thwart would-be assassins (Arnold 1988; Crawford 1970:94,141). The use of umbrellas and parasols by less noble individuals began in the eighteenth century, often credited to Jonas Hanway. Hanway had traveled throughout the British colonies as a philanthropist and brought an umbrella with him when he returned to London (König 2005). This statue of him still stands in Nottinghamshire above an early umbrella shop in the late eighteenth century.

While the exact provenance of this portrait is unknown, it is believed to be a depiction of a young Jane Austin holding a parasol and painted in 1788 by Ozias Humphry.

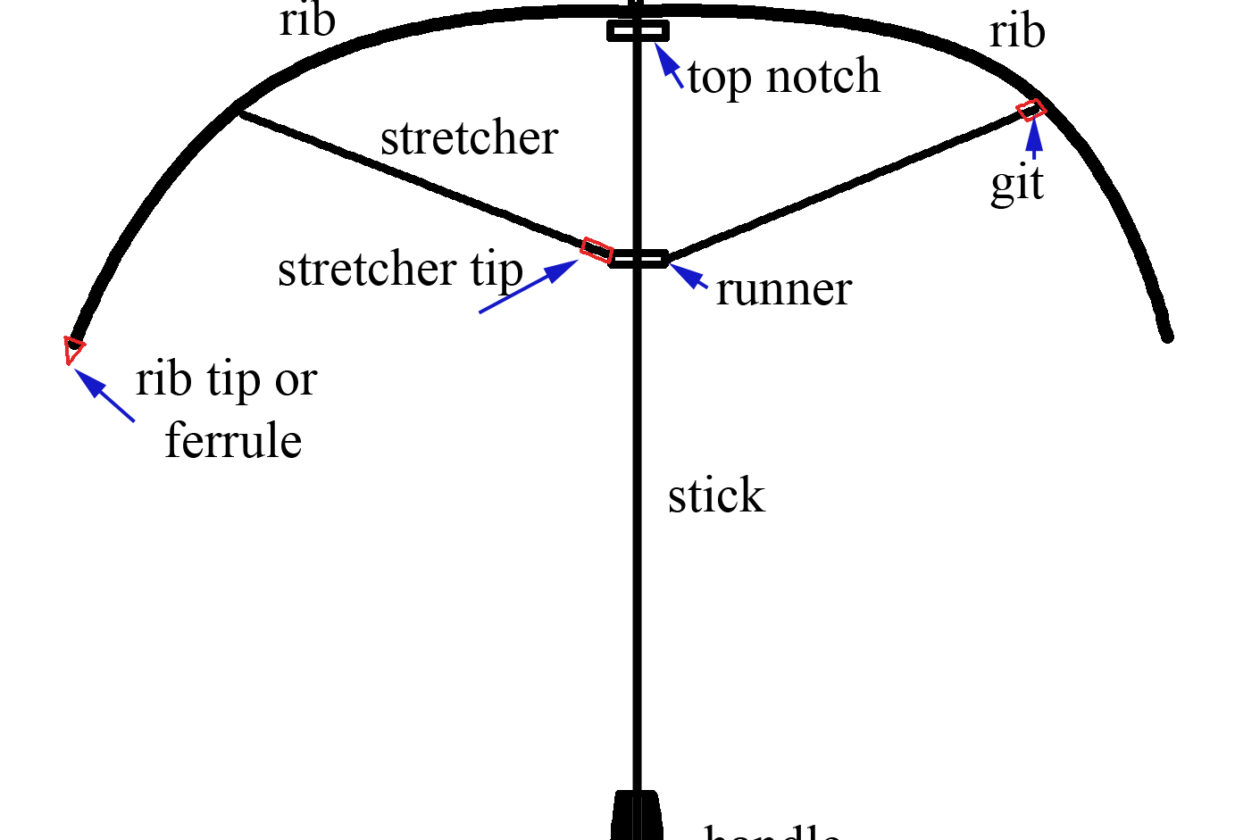

In eighteenth-century France, umbrellas and parasols were made at boursier, or purse-maker, shops (Ross 1994). This plate from Diderot’s encyclopedia (image hosted by Mount Vernon Mystery Midden) depicts the anatomy of these devices. Shops specializing in the manufacture of umbrellas and parasols began to appear in the early nineteenth century (Ross 1994). Parasols produced during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were constructed of oiled silk or cotton stretched over a wood or whalebone frame. They became quite heavy and cumbersome when wet, and some care had to be taken with the whalebone to prevent cracking while drying (König 2005; Sangster 1855:32-33, 58). Numerous patents for improvements on parasols were filed throughout the early nineteenth century in Britain and the United States, including those for the use of metal ribs instead of whalebone; brass ribs were introduced in the 1830s and steel ribs were patented in 1840 and 1852 (König 2005; Sangster 1855:58; Ross 1994). However, there is evidence supporting the production of brass ribbed parasols before the widespread adoption of metals in the 1830s. Jefferson instructed his London merchant-agent Thomas Adams to send him such an item in 1771:

“I must add also ½ doz. pr. Indian cotton stockings for myself @ 10/sterl. per pair. ½ doz. pr. Best white silk do.; and a large Umbrella with brass ribs covered with green silk, neatly finished” (TJ to Thomas Adams June 1, 1771). Jefferson also believed that all of these items could “be bought ready made,” indicating that London craftsmen produced brass ribbed examples with some degree of reliable regularity as early as the 1770s.

The appearance and use of umbrellas and parasols diverged throughout the nineteenth century, the former becoming more specifically adapted for the keeping off of rain, and the latter a gender-specific device suitable for keeping the sun off one’s face to prevent tanning.

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston has an impressive collection of historic parasols. Check out the digital images of their collection here.

This rib tip (left) is unlike the ones found in Site B. It is less elongated, but still contains a fragment of wood inside it. It originates from a late 19th-early 20th disturbance in the Wing of Offices. This outer, more decorative tip (or ferrule) is distinguished from the stretcher tips in that it only has one set of holes located on the inner portion. This parasol tip (right) was also recovered from the Wing, and was found within a trash deposit that dates to after the destruction of the Wing.

We have several parasol/umbrella artifacts in our collections at Poplar Forest, including ribs, stretchers, ferrules, and runners. Rib fragments have been found in our recent landscape excavations, the West Allee, Site B, Site A, the Quarter Site, as well as two from the Wing of Offices. The fragments from the Wing and West Allee originated in layers dated from the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries. These contexts are most likely secondary or tertiary deposits. This means that these artifacts were redposited during earth-moving activities- such as planting holes, landscaping, and utility trenches- after the original deposition of the artifact. As the Wing Re-Analysis is ongoing, we hope to better define the context from which the Wing fragment originates.

A sample (left) of parasol/umbrella rib and stretcher fragments from Poplar Forest. These artifacts were found in (from top to bottom): the Wing of Offices late 19th-early 20th century deposit, Site B antebellum layer, the West Allee in a late 19th-early 20th century planting hole, the Quarter Site, and a mid to late 19th century cobble surface in front of the house from our recent Clumps and Oval beds landscape project. This is a closeup of the stretcher from the Clumps and Oval Beds project. The rectangular-shaped end (right) articulated with the ribs, while the tiny circular hole was affixed to the runner. While the context this artifact was found in dates to a later period, this style of stretcher was produced as early as the last quarter of the eighteenth century (Farrel 1985:32 Fig. 20).

The partial rib from Site B was found within a layer dated to the antebellum period (1840-1860). The Quarter Site, inhabited by enslaved individuals, was occupied from 1790-1812. The context in which the Quarter Site rib fragment was found contained artifacts related to the Jefferson era. Additionally, the site was not subsequently occupied after its abandonment. While the secondary literature on parasols and umbrellas has indicated that copper alloy ribs were not produced until the 1830s, this fragment from the Quarter Site and Jefferson’s specific request for one indicates that some craftsmen did produce them earlier in the eighteenth century.

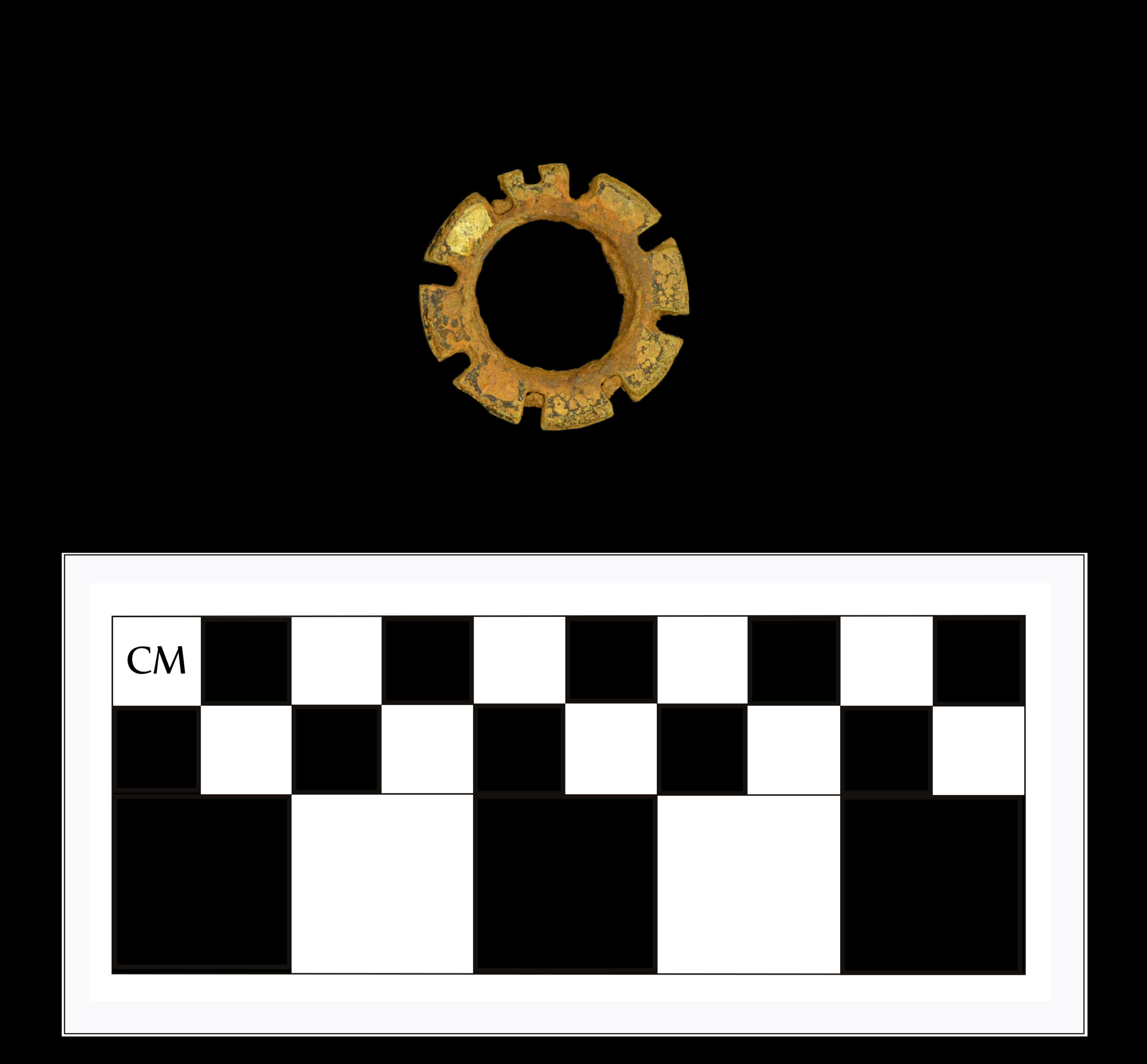

A runner found in a 20th century layer from the Wing kitchen yard. Runners similar to this were produced in the late eighteenth century. Our research into this particular part of parasols is currently ongoing.

Stretchers attached to the central stick runner with a tip similar to the rib ferrules. You can see intact stretchers and their tips on an umbrella here (image hosted by Mount Vernon Mystery Midden, from the Colonial Williamsburg Collection) Several of those from Poplar Forest still contain wood fragments from the parasol’s wooden stretchers. Three of the stretcher tips were excavated in Site A, which includes an antebellum cabin. These three tips (depicted below) are all similar in size and shape and are thus likely to have been from the same parasol (Proebsting and Lee 2012:63). One of these stretcher tips was found in a subfloor pit of the cabin, the others found in close proximity of this pit and chimney features. A similarly shaped stretcher tip (left in image below) was found within the plowzone of Site B, located adjacent to Site A.

As our research continues, we hope to post additional information on our parasol artifacts.

These stretcher tips are from Sites A and B. A closeup (right) of the stretcher tip from the Site A subfloor pit showing the intact wood fragment.

References

Arnold, Janet. 1988. Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d. Leeds: W.S. Maney & Son, Ltd.

Chernow, Ron. 2010. Washington: A Life. Penguin Press.

Crawford, T.S. 1970. A History of the Umbrella. New York: Taplinger Publishing Company.

Farrell, Jeremy. 1985. Umbrellas and Parasols. London: B.T. Batsford, Ltd.

König, Anna. 2005. “Umbrellas and Parasols.” Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion. Valerie Steel, editor. Volume 3. Detroit: Charles Scribner’s Sons, pp357-360.

Notes and Queries. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 24(3): 309-311.

Proebsting, Eric and Lori Lee. 2012. Small Finds, Ceramics, and Landscapes within Virginia and the Greater Chesapeake. Journal of Middle Atlantic Archaeology. 28:55-68).

Ross, Jacqueline Beaudoin. 1994. “Those Parasol Days, late 19th and early 20th Century.” The McCord Museum. http://www.mccord-museum.qc.ca/scripts/explore.php?Lang=1&tablename=theme&tableid=11&elementid=55__true&contentlong.

Sangster, William. 1855. Umbrellas and Their History. London: Effingham Wilson, Royal Exchange.

TJ To Thomas Adams June 1, 1771. Virginia Historical Society.