Archaeology Blog

Being Fussy Never Tasted So Sweet

It’s time to admit a difficult truth…archaeologists are not perfect. We are not omniscient and the artifacts we recover during excavation are sometimes misidentified. One of the many reasons why we continually reexamine our older archaeological collections is to rectify any gaffes and to reevaluate the data from a fresh perspective. Sometimes, we end up with a fun new tale to tell about our sites. This is one of those times.

During a recent reevaluation of artifacts from the 1989 excavations of the Wing of Offices adjacent to the main house at Poplar Forest, a small metal object emerged to tell its story. It is a thin fragment of brass sheeting, cut into a decorative shape, stamped with an art nouveau design of lines and curves and embossed with the word “Whitman”. Originally cataloged as a ‘possible clock hand’, this item has now been properly identified as a fragment of a set of advertising candy tongs that came in a box of Whitman’s Chocolates in the beginning years of the twentieth century.

Fragment of Whitman’s Chocolates advertising candy tongs (left), Poplar Forest archaeological collection. Complete example of Whitman’s advertising candy tongs (right), provenience unknown, image source.

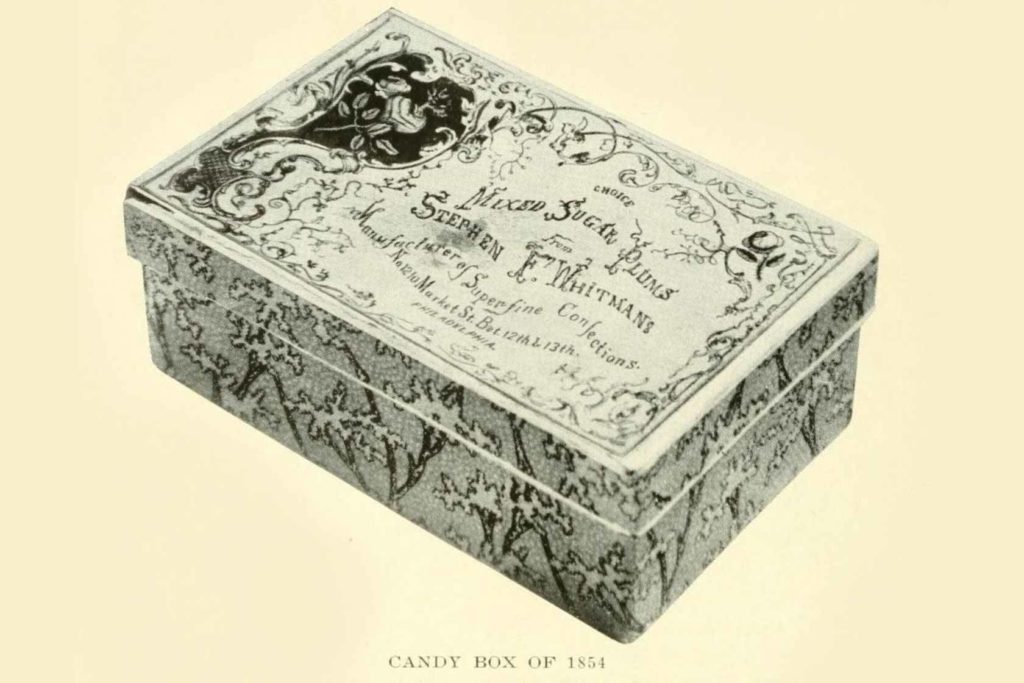

Stephen F. Whitman & Son, Inc. started in 1842, when the eponymous founder opened a small retail “confectionery and fruiterer shop” near the Philadelphia waterfront (Davis 2013). In order to compete in the growing market for sweets in American culture, Whitman’s introduced a new concept to candy sales in 1854: the pre-packaged confection, now known as a ‘trademarked’ package (RS). This initial product was a box of Choice Mixed Sugar Plums (small rounds of flavored boiled sugar) sold in an “elegant box, pink and gilt, lavishly decorated with designs of rosebuds and curlicues” (Goldstein 2015). By the end of the century, Whitman’s had garnered multiple awards at international expositions for ‘product excellence’ and introduced several new pre-packaged products to the markets, including many of the chocolate treats that are still in their repertoire today (RS).

Box of Whitman’s Choice Mixed Sugar Plums, 1854.

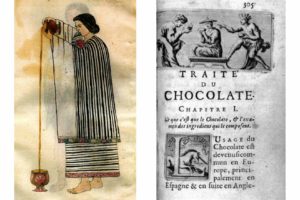

By the late nineteenth century, chocolate had become a staple item in the diet of everyday Americans, but it was not a recent invention. Two spouted ceramic vessels excavated at the Maya site in Colha, Belize and dating to the Middle Preclassic period (600-400 BCE) were analyzed and found to hold substantial amounts of chocolate’s chemical signature theobromine (Powis et al 2002). This evidence reaffirms the understanding that the Maya peoples have been drinking chocolate for thousands of years. It is known that chocolate was consumed across Central America; the Aztec people adopted its use and even made cacao beans a form of currency (ICCO). The first mention of chocolate by Europeans was in the 1502 accounts of Ferdinand Columbus (Christopher Columbus’s son), when he described the “…almonds which the Indians of New Spain use as currency…” (Grivetti and Shapiro 2009). Forty years later, chocolate was introduced to the Spanish court; from there it spread like wildfire throughout the countries of Europe and, via their colonies, to the Americas and the islands of the Caribbean. An increase in both supply and demand, combined with an emerging global trade market, encouraged innovation in the chocolate business (Grivetti and Shapiro 2009). Chocolate quickly became a familiar ingredient to people of the 18th century, but the short shelf-life and laborious production process was still an expense that only the upper classes could afford. Chocolate had taken its first steps to becoming a central element of the Western diet, but the Industrial Revolution would catapult it the rest of the way there.

Aztec woman pouring chocolate, Codex Tudela, 16th century | Page from De l’Usage du Caphe du The et du Chocolate, P. S. Dufour, 1671, “Traits of Chocolate.”

Chocolate is made from the ground seeds of the cacao tree. The seeds (beans) grow inside large pods, which are harvested, fermented, and dried before being sorted, packed, and shipped to chocolate manufacturers (Vukovic 2004). At the factory, the beans are roasted and ground until the heat from the process causes them to separate into its two constituent parts: cocoa liquor (the mass of the chocolate) and cocoa butter (the oil from the beans) (Chapman 1917). The cocoa liquor is then mixed with sugar, a small amount of the cocoa butter, and flavorings and put through couching and tempering processes before being molded into its final products (Chapman 1917, Vukovic 2004).

Workers in Whitman’s factory, February 19, 1921.

For millennia, the process of turning cacao beans into chocolate was a lengthy process that needed to be performed by skilled laborers (Chapman 1917). Thus, most chocolates were made by the same people who sold them, in small, family-owned shops (many examples available in Grivetti and Shapiro 2009). The first chocolate ‘factory’ was established by Joseph Fry in 1761, but it wasn’t until his grandsons ran the company that it became the leading producer of chocolate in Britain (Goldstein 2015). With the growth of standardized and mechanized production methods throughout the retail market, more companies were able to produce large amounts of chocolate candies for a reasonable cost, allowing it to permeate the lives of ordinary people. An 1894 guide to the city published by the City of Philadelphia proclaimed “Cocoa, once the luxury of the wealthy and exclusive, has become an article of food for the people, supplanting coffee and tea upon thousands of tables, and, in some form, found in nearly every household.” (Taylor and McManus 1894). Over a quarter of the world’s cocoa production in 1911 was consumed in the United States alone (Chisholm 1913).

Whitman’s retail store, Philadelphia, PA, 1894.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania was the third largest producer of total manufactured goods and the largest producer of candy in the United States (Chisholm 1913). Whitman’s had become the leading chocolate maker in Philadelphia and one of the largest producers of confections in the country (Chapman 1917). But the candy industry was thriving; chocolate makers had to find a way to entice consumers to purchase their product over that of a competitor. Thus was born the great age of candy advertisements.

A contributor to International Confectioners gave the following advice to his fellow candy sellers:

“The eye must be arrested… the talk that goes with it, in the form of well executed and worded window cards, should be of the bullseye kind, straight, strong, forcible and convincing without ‘flim-flam’ or a straining after unusual or striking rhetorical effects. In a word, the cards in a window display should convince with their candor and common sense, for the great mass of people, rich or poor, have simple minds and must be talked to in a simple way – Aim low.” (Blakely 1915)

This advice, though condescending and cynical in its estimation of the consumer’s intellect, does exemplify the general principles that chocolate ads seem to have followed in the early twentieth century; they often simply stated the superiority of their product while boxing the candy in elaborate packages. The emphasis in the ads was placed less on any new food trends than on the rising importance of novelty and convenience (Blanke 2002).

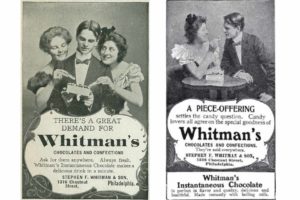

The brass candy tongs represented in the Poplar Forest archaeological collection were included as a sort of advertisement inside some of Whitman’s boxes of chocolates. They were placed flat underneath the lid for convenience of packing, but the consumer could easily bend them into shape upon opening the box at home. The first known advertisement illustrating the use of these tongs was run in 1899 and depicts a handsome young man offering a box of Whitman’s chocolates to two lovely ladies, one of whom is eyeing him flirtatiously. All three figures are stylishly dressed and the text is surrounded by elaborate whorls and scrolls, lending an air of sophistication and elegance to the ad that the creators clearly hoped would transfer to people’s opinion of the product.

Advertisement for Whitman’s Chocolates and Confections, 1899. Ayer Advertising Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. | Advertisement for Whitman’s Chocolates and Confections, 1899.

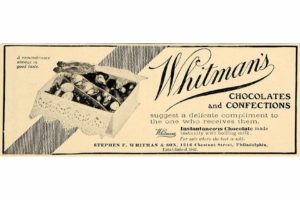

By 1901, Whitman’s had begun to narrow their marketing focus to the quality of the product itself and started to present it as the perfect gift for a special occasion. Ads featuring slogans such as “Always in good taste.” and “For sale where the best is sold.” continued to include illustrations of the stamped brass tongs like the ones found at Poplar Forest. In turn-of-the-century Western culture, high-society etiquette demanded a dedicated utensil for each dish served to a guest. By providing such a utensil (with the company’s name conveniently stamped in beautiful script on its face) in each of their fancy boxes, Whitman’s allowed each consumer to feel as though they were participating in a high-class ritual that they could only get by buying Whitman’s high-quality product.

Advertisement for Whitman’s Chocolates and Confections, 1906.

In the early 1900s, the rapid commercialization of food production led to a (legitimate) concern for the safety of machine-made foods that used to be made in small family shops or in one’s home. Women’s magazines encouraged them to buy only high quality (i.e. high-priced) products as they were more likely to be safe (Kawash 2009). Walter P. Sharp and other company executives at Whitman’s recognized this movement and altered their marketing strategies accordingly. In 1907, Whitman’s began offering direct distribution to customers and began to place their products with only a single or the “better” drug stores in town. The “Fussy Package for Fastidious Folks” advertising campaign began in 1911 and was still in use as of 2005 (NCSA). The ‘Fussy Package’ was a specific collection of Whitman’s higher-prestige options including chocolate-covered nougats, molasses chips, almonds, marshmallows, neapolitans, and caramels (but “no cream centers nor bonbons”). It was also “Guaranteed fresh, pure, perfect.” and came with a money back guarantee; a bold statement in the company’s belief in the quality of its product that was not supported by many other manufacturers of the era (NCSA).

Advertisements for Whitman’s Chocolates and Confections, late 19th and early 20th centuries.

This thread of advertising worked exactly as it was intended. Boxes of Whitman’s chocolates flew off the shelves and the ‘Fussy Package’ became a staple in the Whitman’s catalog (the nut-centered candies are still sometimes referred to as the ‘Fussy Chocolates’). It was so popular that Whitman’s even tried to trademark the word ‘fussy’ in 1910 (the application was denied).

Walter P Sharp, inducted into the Candy Hall of Fame in 2005, NCSA (left).Whitman’s Chocolates and Confections Sampler, as it appeared in 1912 (right).

Walter Sharp, taking over the company’s presidency in 1912, introduced the Whitman’s Sampler, an assortment of the company’s best-selling chocolates. Tradition holds that he was inspired to design the now-iconic look of the Sampler box by a framed cross-stitch sampler hanging in his grandmother’s home. A spokesperson for the company on its centennial anniversary said “The original 1912 package had an aged, yet ageless look suggesting the box had been around for 100 years, giving first-time buyers a sense of confidence in their gift choice,” (Lindell 2012). Additional innovations included wrapping each box with cellophane to preserve freshness and including an index showing each candy inside each box (Davis 2013).

With the innovations in packaging, came a different tactic in advertising. The Sampler was promoted as an affordable treat for the everyman, but still kept the quality associated with the Whitman’s name. Consumers responded, and by 1915 the Sampler was the most popular product in the Whitman’s line.

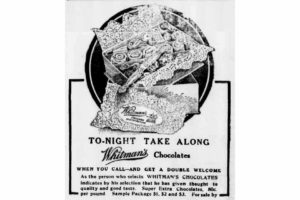

A review of surviving advertisements shows a demise of the Whitman’s candy tongs near the onset of the First World War. An ad in the January 11, 1917 edition of The Roanoke News (1878-1922) shows the familiar box of Whitman’s Chocolates, open with an unfolded set of candy tongs on top. The text below reads “When you call-and get a double welcome. As the person who selects Whitman’s Chocolates indicates by his selection that he has given thought to quality and good taste”. This is the latest advertisement showing the tongs that this author was able to locate. There is no documentation available as to the exact date when Whitman’s ceased to include candy tongs in their Fussy Package boxes. Perhaps the company decided to reduce expenditure on that particular line of packaging in lieu of the popularity of the Sampler. Perhaps the onset of the First World War and the resulting demand for metals for the war effort made the enclosure of brass tongs too costly. Whatever the reasoning, all traceable Whitman’s Chocolates ads after 1917 depict people enjoying their treats sans tongs.

Advertisement for Whitman’s Chocolates, 1917, The Roanoke News, January 11, 1917.

Perhaps Thomas Jefferson was right when he wrote that “…by getting it good in quality, and cheap in price, the superiority of [chocolate] both for health and nourishment will soon give it the same preference over tea & coffee in America which it has in Spain…” (letter to John Adams, 1785).

The fragment of candy tongs found at Poplar Forest cannot tell us about an individual person who lived here. We don’t know who bought the box of chocolates, or for whom, or for what occasion. But we do know that, whatever their motivations, both giver and receiver were participants in the much larger story of America’s sweet tooth.

Blakely, J. W. 1915. Window Dressing. International Confectioners Vol 24, January.

Blanke, David. 2002. The 1910s. American Popular Culture Through History series. Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood Press.

Chapman, Ellwood B. 1917. The Candy Making Industry in Philadelphia. Issued by The Educational Committee of the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Chisholm, Hugh. 1913. The Britannica year-book, 1913 – a survey of the world’s progress since the completion in 1910 of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. New York, Ecyclopaedia Britannica.

Davis, George. 2013. A candy-coated history: How the iconic Whitman’s sampler came to be. Journal of Humanitarian Affairs. March 1, 2013. http://journalofhumanitarianaffairs.blogspot.com/2013/03/a-candy-coated-history-how-iconic.html

Goldstein, Darra. 2015. The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 156-158.

Grivetti, Louis E. and Howard-Yana Shapiro, ed.. 2009. Chocolate: History, Culture, and Heritage. Hoboken, New Jersey, Wiley.

International Cocoa Organization. “Chocolate Use in Early Aztec Cultures”. https://www.icco.org/faq/54-cocoa-origins/133-chocolate-use-in-early-aztec-cultures.html [Abv ICCO]

Kawash, Samira. 2009. “Home Made vs. Store Bought Candy”. candyprofessor.com, October 14, 2009. https://candyprofessor.com/2009/10/14/home-made-vs-store-bought/

Lindell, Crystal. 2012. Ageless at 100 – Whitman’s Sampler: America’s most famous box of chocolates celebrates its centennial. Candy Industry, April 2012. http://www.candyindustry.com/articles/85153-ageless-at-100—whitman-s-sampler-

National Confectionary Sales Association. “Walter P. Sharp”. http://candyhalloffame.org/CHoF/inductees/2005/walter-p-sharp.shtml [Abv NCSA]

Powis, Terry G., Fred Valdez, Jr., Thomas R. Hester, W. Jeffrey Hurst and Stanley M. Tarka, Jr. 2002. Spouted Vessels and Cacao Use among the Preclassic Maya. Latin American Antiquity 13(1): 85-106.

Russel Stover. 2016. Whitman’s Timeline. http://www.russellstover.com/whitmans-timeline. [Abv. RS]

Taylor, Frank H. and William B. McManus. 1894. The City of Philadelphia as it Appears in the Year 1894: A Compilation of Facts supplied by Distinguished Citizens for the Information of Business Men, Travelers, and the World at Large. Prepared under the auspices of the Trade League of Philadelphia. George S. Harris & Sons.

Vukovic, Heidemarie. 2004. Crazy about Chocolate. The Herbarist 70:62-65.